Although artificial intelligence (AI) might seem like the future frontier; it’s a present reality. For many organisations, it’s already a reliable source of income. According to Gartner’s 2019 CIO Agenda survey, the proportion of companies that deployed AI between 2018 and 2019, grew from 4% to 14%.

However, AI opens as many opportunities as it creates challenges.

With the growing use of AI and machine learning (ML) technologies by enterprises, there is also growing concern regarding data bias, providence and regulations. Moreover, COVID-19 has created a huge demand for AI tools, accelerating the need for solutions for these issues.

Tessella is one of the companies providing answers, utilising its 40 years of data science expertise for this purpose. An international data science consulting services company based in Oxfordshire, it was acquired by Altran in 2013 and is now part of Capgemini. Some of its most famous projects include the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter and the University of Oxford’s real-time Ebola tracking map.

Matt Jones, Data Science Strategist at Tessella, tells Digital Bulletin what attracted him to join this company from GSK in 2014: “I was actually a client and I was constantly impressed by the people there. I also recognised at that time how important data science, AI and analytics was becoming to us at GSK, but also the general marketplace, and I wanted to be a part of that.”

As a Data Science Strategist, Jones helps Tessella’s clients undergo digital transformations using AI and data analytics. “What Tessella is all about is building expert systems for engineers and scientists to use, and a lot of this is acquiring value for data,” Jones says.

Data is incredibly valuable and holds immense power. However, part of Jones’ role is also to make sure that this data is being used responsibly and keep AI tools from inheriting human biases.

“I do note, particularly when I’m reading the press that, when the machine gets it wrong, people are very quick to point the finger at the AI,” Jones reflects.

The American COMPAS (Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions) system and Amazon’s CV screening tool are two recent examples of this. COMPAS was criticised because of its tendency to label Black people as being more likely to commit a second criminal offence, while Amazon’s CV screening tool often recommended male CVs for technical roles over similar female ones.

“In all these cases, the machine did exactly what is designed and trained to do,” Jones says. “The machine doesn’t know what racism is. It inherited its bias from the humans that built it.”

To avoid data bias, it is necessary to make sure that the data used to train AI reflects the real world. Moreover, the data has to be obtained from reliable sources to be accurate and representative.

“If the data doesn’t come from a secure and proven source, then it shouldn’t be used,” Jones states. This is where data providence comes into play.

Data providence refers to the historical record of data, and it’s used to verify its origin and use. Some of the most common ways of keeping track of data providence are blockchain, workflow capture and auditing.

“I thoroughly believe you need to understand where your data is coming from,” Jones says. “And you have to have confidence that it’s been collected, it’s been sourced, it’s been manipulated responsibly.”

Unfortunately, this is not always the case. One recent example would be Clearview AI. This facial recognition AI was trained from a database of more than three billion images taken from the internet. After a security breach, the company’s database and list of clients were exposed, revealing that the AI had been used by retailers, police forces, and even individuals.

Avoiding situations like this one is the aim of governance models. Although most countries don’t yet have specific laws and regulations to the use of AI, the need for them has been a constant topic of discussion in international organisations such as the EU and the UN.

In Jones’ view, the implementation of AI governance has little to no cons. “I don’t understand why you would not have IT governance,” he says. “If you don’t have a governance model, then the introduction of any new technology, particularly something like AI, can be chaotic and potentially undermine any benefits.”

The need for AI governance is more pressing now than ever, as COVID-19 has drastically accelerated the use of this technology. “We’re making years of progress in months, and AI is at the centre of that”, Jones states.

However, Jones warns that AI “don’t add any value unless it’s being used”. And, more often than not, designing a model is much easier than implementing it, particularly when scaling it.

If you don’t have a governance model, then the introduction of any new technology, particularly something like AI, can be chaotic and potentially undermine any benefits

Over recent years, Tessella has worked with many clients which have struggled precisely with this step. They have built internal data science capabilities and teams that have developed promising proofs of concept. However, they still fail to see any respectable ROI out of it. Jones is familiar with this scenario and likes to call it “being trapped in a proof of concept purgatory.”

There are several roads that lead to this “purgatory”, including a lack of communication between software engineers and data scientists, or companies’ tendency to get lost in the possibilities that AI provides, instead of solving specific business’ problems.

“For any AI model to be useful, it has to be wrapped in useful software,” Jones explains. “When I talk to clients, I ask them to avoid scenarios where we want to see what we can do with the data. That’s a great academic exercise. But what I would want them to do is identify the business’ needs first, the challenges the business has first, and then get the data, look at the data and understand what they can do with it to prove value, and then build a proof of concept and move it forward.”

Another way out of this “purgatory” is to include people in these AI teams that understand both the data and the business needs and can mediate between both teams. Jones calls them “translators”.

By doing these two things, prioritising business needs and ensuring accurate communication between teams, companies can utilise the full potential of AI as a digital acceleration and leader in digital R&D.

“Modern AI is now taking the lead in designing and delivering new products and services into markets,” Jones says. “From product research and development to manufacturing, but also sales, delivery, logistics, and supporting these products once out there.”

For example, in the manufacturing sector, AI drastically reduces costs by creating models in clay that can be easily tested, and even make suggestions of candidate products or formulations. RPA (robotic process automation) is also growing bigger by the minute. RPA allows for the automation of many manual tasks which are tedious and ‘data-centric’ such as insurance claims, through the use of image analysis.

However, in current times one of the most demanded uses of AI is in the healthcare industry, to which Tessella is no stranger. In 2015, the company participated in a project alongside the University of Oxford that used data analytics to predict the spread of Ebola. The resulting AI could analyse social media data to generate maps that showed real-time maps of the disease spread.

The most fascinating aspect of this project was, however, the trust aspect. “If the AI didn’t know then it wouldn’t present a guess as an answer,” Jones explains. “Epidemiologists were confident that it was never going to present misinformation, and that increased their level of trust in the AI.”

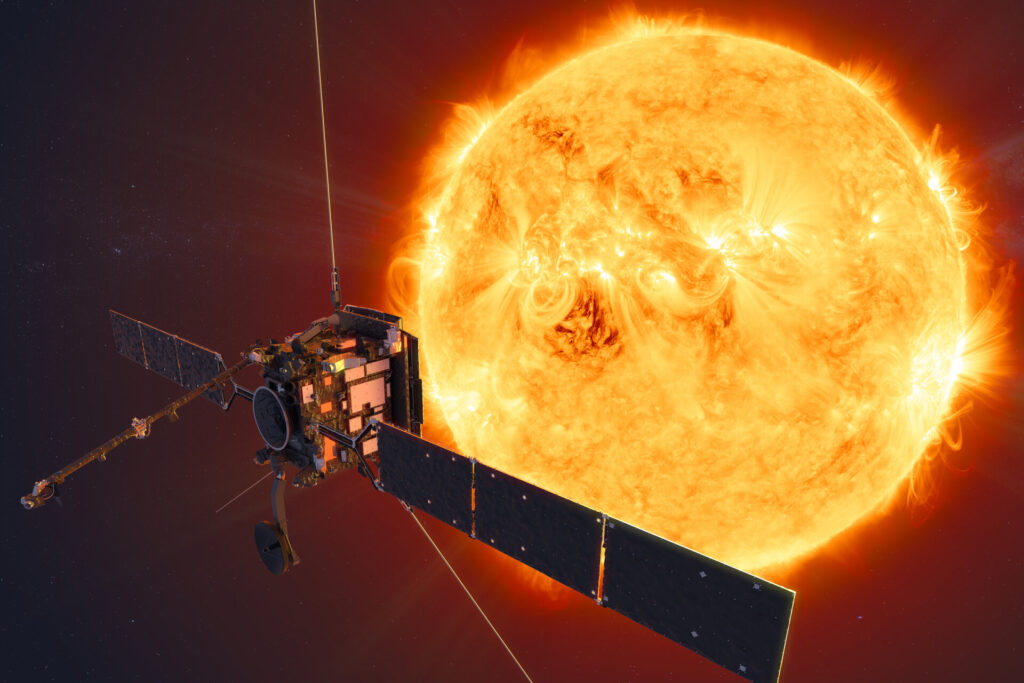

Although AI has incredible potential, it is not always the perfect solution. A key to successfully utilise AI is to know how to combine it with traditional tools. “The ESA’s Solar Orbiter is a perfect example of choosing the right tools for the right job in hand,” James says.

The most interesting tool that Tessella developed for the ESA’s Solar Orbiter was the Altitude and Orbital Control Systems (ACOS). This tool was used to automatically calculate the distance between the aircraft and the Sun, which could not deviate more than six degrees – any more would mean the spacecraft was destroyed. To do so, Tessella combined AI with classical physics and statistics.

Although AI might not be the solution for everything, its rise to prominence has been rapid, meaning Jones refuses to consider it a ‘future’ technology.

“AI is fairly ubiquitous in everything that we do,” he says. “If it’s got a screen on it, then it’s got AI, most likely. It’s a technology that has a future, of course, but it’s very very now”.

If AI’s present is exciting, its future is even more promising. Jones believes that, in the next five years, AI will become central to our daily lives, from personal assistance to healthcare, as well as in city and resource-management.

However, although AI is an incredibly powerful tool, it’s also just that. It’s power lies in its correct use and application. AI will be a tremendous digital accelerator, but there needs to be governance that regulates it and ensures its accuracy.

“It’s like a hammer,” Jones says. “It’s all driven by humans.”