Discourse on the future of manufacturing is dominated by technologies like advanced artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things and robotics.

The concept of 3D printing has been around far longer yet has remained in the background, sometimes perceived as a niche requirement for a small segment of industry. A technique first developed in the 1980s, it has operated steadily at the edge of the enterprise market for the last 30 years.

Hardware and software developments in more recent times, however, mean that industrial 3D printing – or additive manufacturing – is appearing in many more use cases. Since 2013, corporate investment in 3D printing has increased each year, with the likes of GE and Siemens making their own financial bets on the technology.

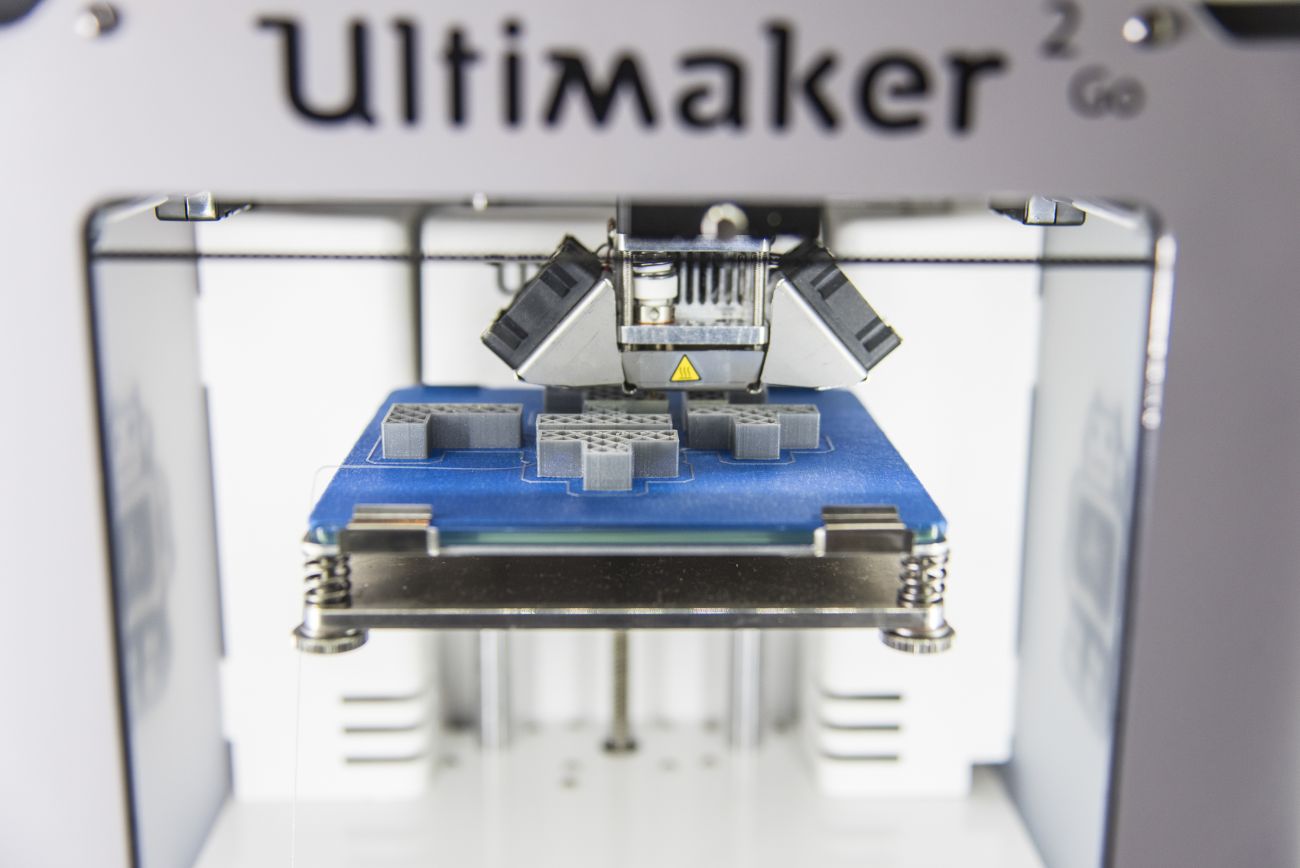

Paul Croft (pictured), as a Director for the UK arm of leading 3D printing hardware and software builder Ultimaker, has witnessed this upturn and believes we are now finally ready to realise 3D printing’s enterprise potential.

“People who have been in the industry are starting to see where the value opportunities are,” he explains. “It’s no longer about prototyping. We’re now talking abundantly about tooling and manufacturing aids, and as a market profile that moves from billions to trillions.

“You don’t have to go out and spend half a million quid on a big, metal 3D printer to say you’ve got a presence in 3D printing – actually you can invest £5k in a reliable piece of kit which allows you to develop an understanding of the benefits of additive manufacturing across your business-specific value chain.

“People are seeing an ROI. It’s no longer research projects and speculations; it’s starting to have an impact in the design rooms, on the conference floor and also importantly in the boardrooms, where people can see the impacts on profit and loss. That’s what is really driving the adoption.”

Industries at the forefront of this adoption include automotive and aerospace, outlines Croft. Forbes, in a recent review from its Technology Council, pinpointed these two sectors along with a number of other areas ripe for 3D printing disruption, including construction, bioengineering and clothing and textiles.

Croft speaks of a particular Ultimaker case study with Volkswagen to demonstrate his point; the largest automaker in the world has been exploring how 3D printing can drive efficiencies in its manufacturing plants.

“It started a pilot scheme looking at where it could reduce its tooling costs, or manufacturing aid costs, across the production line,” he reveals. “But from what started out as an initial research project, it went on to save 91% on tooling costs and 95% on its tool development time.

“If you start applying those numbers to the numbers that Volkswagen is talking about, and it very quickly multiplies up to hundreds of thousands in savings. Then, if you then multiply that by the number of sites Volkswagen has globally for all of their different brands, then you’re talking millions and millions worth of savings with very little capital outlay.”

A truly connected factory of the future that achieves anything will have to rely on 3D printing and additive manufacturing

On a similar scale in the aerospace industry, Ultimaker is now working with Airbus on manufacturing use cases across a number of its sites. But what are the solutions making such a difference for these well-established companies?

Take the Ultimaker example; a company with resellers in over 50 countries and an open source community boasting more than 50,000 members, its range of hardware delivers 3D printing for the industry-grade materials required by the likes of Volkswagen and Airbus.

It is through its Cura software, however, that Ultimaker is able to deliver such a compelling pitch to clients interested in incorporating additive manufacturing at scale. Once the digital model for a product is drawn up, Cura translates that model into instructions for whichever 3D printer is being deployed. This capability opens up a broad market for Cura and Ultimaker.

“In layman’s terms, Cura is effectively a set of coordinates with instructions accompanying it which instruct the printer where to deposit the material layer by layer, to build up the model that has been originally designed or scanned,” expands Croft.

“It’s still, to this day, used by many of Ultimaker’s hardware competitors, which is a fantastic testimony to the power of the software. Last year, we were celebrating over one million unique users of Cura worldwide.”

Leading hardware and software can only go so far in the hands of untrained workers, however. That is why Croft has been the driving force behind the ‘CREATE Education Project’, with Ultimaker building a collaborative platform that provides resources and support to introduce 3D printing into classrooms.

Aligned with the extensive support services offered to professionals out in the field – Ultimaker’s products come with lifetime technical support and customer service – and it’s clear that skilling today’s and tomorrow’s workforces in 3D printing is vital to its sustained adoption.

“Do I think the skills are there? Yes I do. Do I think that those skills need tweaking and highlighting and aligning to the opportunities that are obvious to people who have been in this industry? Yes, 100%,” admits Croft.

“3D printing can go straight into virtually any organisation that has engineering or manufacturing, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that they know how to get the optimum settings for the printer, for example. There are new sets of skills that are developing on top of the ones that already exist.”

Adopters will also have to keep pace with the technological developments of the products themselves. Machine learning algorithms are increasingly common in generative design processes for 3D printing, helping to explore all possible permutations of a proposed model and suggesting the optimal design pathway.

This increases efficiency and reduces costs for the customer, two key factors for widespread uptake. Croft likens this process to evolution in the natural world.

“When I’m explaining it to a larger audience, I would talk about how nature has had billions of years to evolve the best solutions for stuff,” he says. “For however long it has been, we’ve not had the tools or the manufacturing techniques to be able to realise these efficiencies.

“That has changed over the last few years. Now, thanks to AI algorithms, machine learning and software solutions like Autodesk Fusion 360, you can now set certain parameters around mechanical properties and then allow the algorithms to effectively propose, based on your instructions, a more optimised model.

“It’s a really exciting time. Organisations that have made the initial step into additive manufacturing are looking now into how to optimise that.”

Croft takes it one step further, emphasising his belief that 3D printing will be fundamental to the factories of the future.

“Industry 4.0 is my third slide in the presentations that we do,” he concludes. “Once the value saving and opportunities really start to be in the market, I think there will be an awful lot of top-down decision making which will increase the rate of adoption even faster than it is today.

“A truly connected factory of the future that achieves anything will have to rely on 3D printing and additive manufacturing.”